How Negative Self-Talk Develops and How to Help Change It

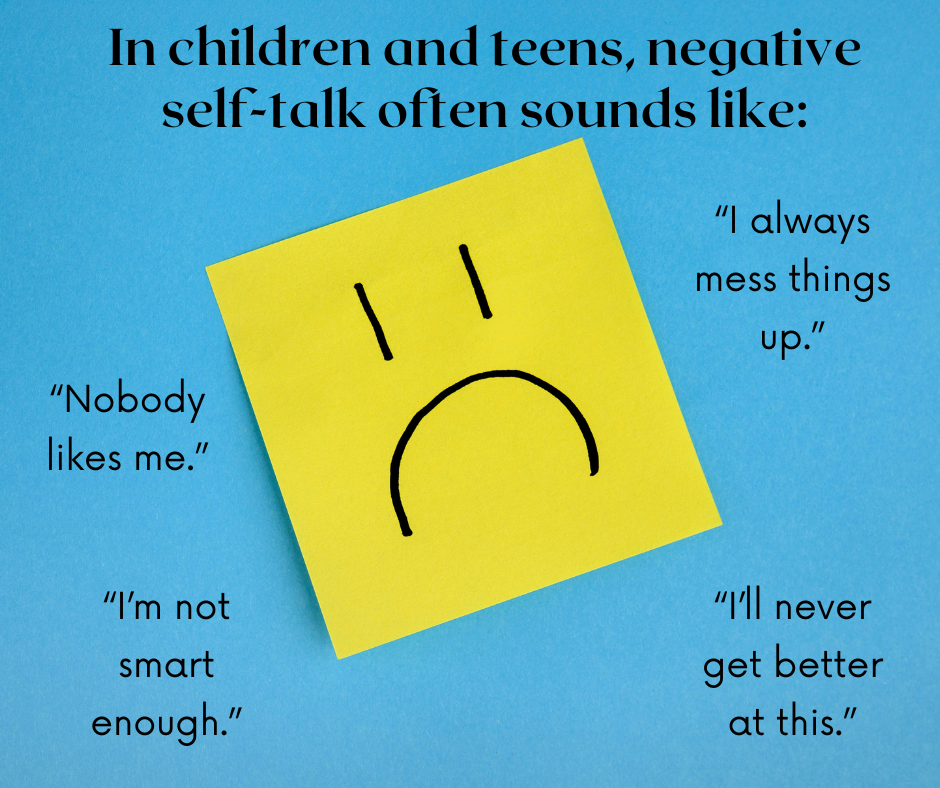

Have you ever heard your child say, “I’m bad at everything,” or your teen mutter, “I’m so stupid,” after making a small mistake?

That inner voice, often called negative self-talk, can quietly shape how children and teens see themselves, their abilities, and their future. Over time, it can influence confidence, motivation, and emotional well-being.

The encouraging part is this. Negative self-talk is learned, which means it can also be unlearned. With the right support, children and teens can develop a kinder, more balanced way of talking to themselves.

What Is Negative Self-Talk?

Negative self-talk is the internal dialogue that focuses on perceived failures, flaws, or fears.

Negative self-talk can sound quiet, but it has a powerful impact on how children and teens see themselves.

When these thoughts repeat over time, they can impact self-esteem, emotional regulation, and willingness to try new or challenging things.

How Negative Self-Talk Develops

Negative self-talk does not come out of nowhere. It usually develops through a combination of experiences, environment, and normal developmental changes.

Repeated experiences of criticism or perceived failure

Children naturally try to make sense of what happens around them. When they experience frequent correction, comparison, or disappointment, they may begin to internalize those moments as statements about who they are rather than what happened.

A single thought like, “I made a mistake,” can slowly turn into, “I’m bad at this.”

Modeling from adults and peers

Children learn language and thinking patterns from the people around them. When they hear adults or peers talk negatively about themselves, such as “I can’t do anything right,” they may adopt similar patterns of self-talk.

Developmental changes in thinking

As children grow, especially during late elementary and middle school years, they develop more abstract thinking and self-awareness. While this allows for reflection, it can also lead to harsher self-judgment.

Teens are especially prone to patterns like:

Overgeneralizing: “I always fail.”

Mind-reading: “Everyone thinks I’m weird.”

All-or-nothing thinking: “If I’m not perfect, I’m a failure.”

Stress, anxiety, or big life changes

When children feel overwhelmed, anxious, or out of control, negative self-talk often increases. It can become their brain’s way of trying to explain uncomfortable feelings, even when those explanations are inaccurate or unkind.

Why Negative Self-Talk Matters

When negative self-talk goes unaddressed, it can contribute to:

Low self-esteem

Anxiety or emotional withdrawal

Avoidance of challenges

Perfectionism or fear of failure

Emotional outbursts or shutting down

Over time, a child’s inner voice can become the filter through which they interpret their experiences.

How to Help Change Negative Self-Talk

Changing negative self-talk is not about forcing positive thinking. It is about building awareness, compassion, and flexibility.

Help children notice their inner voice

Many kids are not aware of how harsh their self-talk can be. Gently helping them notice it is the first step.

You might ask:

“What did your brain say when that happened?”

“If that thought had a voice, what would it sound like?”

Younger children may benefit from drawing or naming their “thought voice.”

Separate the child from the thought

An important skill is helping children understand that thoughts are not facts.

You might say:

“That sounds like a really mean thought.”

“Just because your brain says it does not mean it is true.”

This creates distance from the thought and reduces shame.

Teach more balanced self-talk

Rather than jumping straight to positive statements, focus on realistic and compassionate ones that feel believable.

Examples include:

“This is hard, but I’m learning.”

“I made a mistake, and that’s okay.”

“I do not have to be perfect to be good enough.”

Use play and creativity

In counseling, negative self-talk is often explored through play, art, games, storytelling, and role-play. These approaches allow children to express their thoughts safely without pressure to find the “right” words.

Reinforce effort rather than outcomes

Focusing on effort instead of results helps reduce self-criticism and supports resilience.

Instead of saying, “You’re so smart,” try, “I noticed how hard you worked on that.”

Helpful Resources for Parents and Caregivers

Books for parents

Mindset by Carol Dweck, PhD

Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child by John Gottman, PhD

The Whole-Brain Child by Daniel J. Siegel, MD, & Tina Payne Bryson, PhD

Books for children and teens

What to Do When You Worry Too Much by Dawn Huebner, PhD

What to Do When Your Brain Gets Stuck by Dawn Huebner, PhD

My Thoughts Are Clouds by Christine Herbert

Stuff That Sucks by Ben Sedley, PsyD

Online resources

How Play Therapy and Counseling Can Help

For some children and teens, negative self-talk can feel hard to shift on their own. Counseling offers a supportive space to slow down, notice patterns of self-criticism, and build more balanced ways of responding to mistakes, stress, and big emotions.

Through play therapy, children can explore their thoughts and feelings using play, art, stories, and imagination rather than needing to explain everything with words. Negative self-talk often appears through themes or characters in play, allowing therapists to gently support self-compassion, emotional awareness, and confidence in ways that feel natural and safe.

At Reach Counseling, our therapists use developmentally appropriate, relationship-based approaches, including play therapy, to help children and teens learn to relate to themselves with more kindness and flexibility.

A Final Thought for Parents

If your child struggles with negative self-talk, it does not mean you have done something wrong. It means your child is human and learning how to navigate a complex world. With patience, support, and sometimes professional guidance, that inner voice can become gentler and more supportive over time.